Last week, I made a political comment on Instagram that set my account on fire.

What did I say that was so controversial?

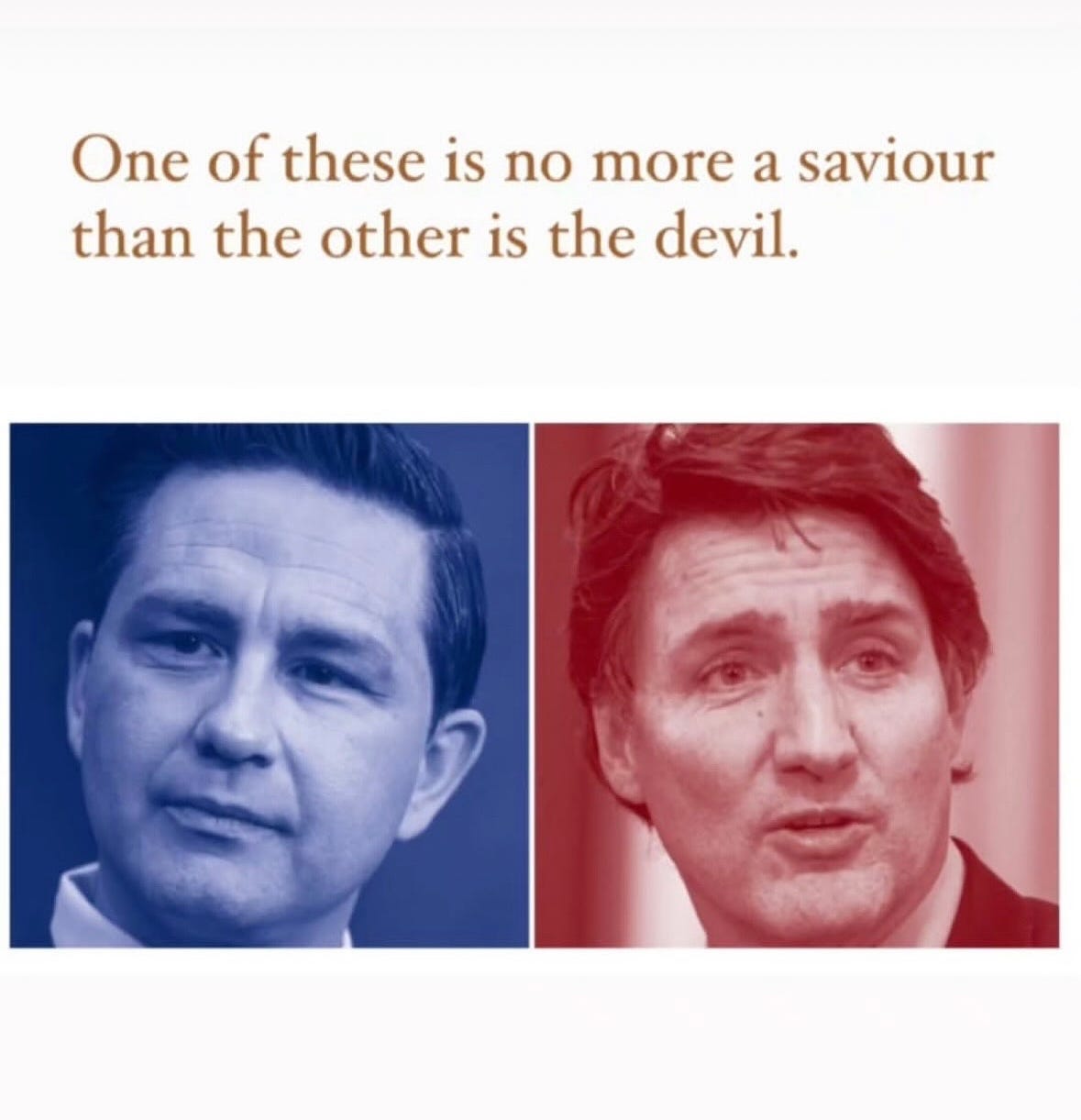

Here is the post:

I didn’t say we should distrust Pierre Poilievre, I didn’t say we shouldn’t vote for the CPC (Conservative Party of Canada) when we have the chance, and I didn’t say that Poilievre would be as bad for our country as Chrystia Freeland or Mark Carney or any of the other, now, usual suspects. I said we should be cautious about seeing Poilievre, or any other political figure, as our saviour.

My point was that hero-worship, like villain-loathing, can become a psychological crutch, allowing us to be caught off-guard by shelving our attention and acting as a surrogate for the critical thinking and intentional action we need to be doing ourselves.

I assume that one of the reasons my comment was so provoking is because it felt, to some, like a wet-blanket on our best chance at better federal leadership. And that matters deeply. It matters to people who can’t feed their families; it matters to those who have been maimed by, or lost loved ones to, inane COVID-19 policy; it matters to the freedoms we are losing every day; and it matters to whether or not we will continue to have a country to call home.

The suggestion that we should hold off throwing our enthusiastic (but probably myopic) support behind the only non-Liberal capable of becoming our next Prime Minister feels dangerous in our current climate. And perhaps it is.

But this raises a bigger concern about a shift happening in the freedom community. After mounting a united front 4 years ago against attacks on our freedoms, the ‘freedom community’ seems to be going the way of all slightly stale alliances — knit-picking, sneering and shaming, factions forming within the silos, dissension growing in the ranks.

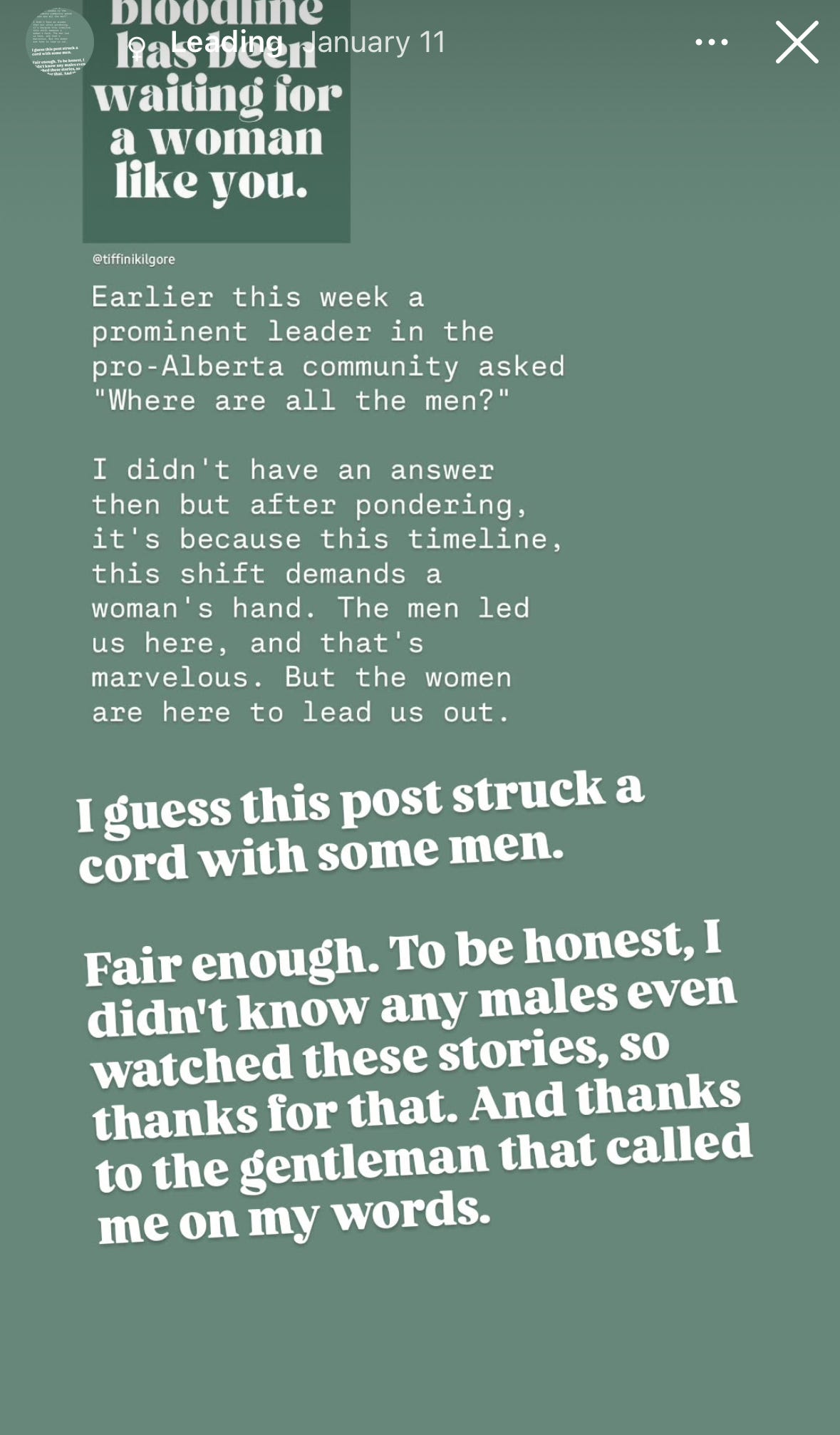

Last week, Lisa Szabon (creator of Fear|Less Changemakers) was berated for an Instagram story in which she suggested that “this timeline, this shift demands a woman’s hand.” “The men led us here, and that’s marvelous. But the women are here to lead us out.”

The predictable shaming ensued. How dare she fuel “divisive rhetoric”? How could she not acknowledge all the work some men are doing?

It’s hard to watch our precarious solidarity start to crumble when we need it the most. But there is nothing surprising about this.

Alliances — usually temporary arrangements against a specific common threat — emerge for a number of reasons. In the years following WWII, European nations aligned to protect themselves from resurgent Nazism, the Soviet Union and communist expansion. Truckers and their supporters from all corners of Canada united in Ottawa in 2022 to challenge the encroachment of government powers into our personal lives. When threatened, as states or as individuals, we tend towards alliances to defend ourselves against a powerful aggressor.

But alliances involve their own risks, their own inherent instability: infighting, “free-riding,” entanglement with unwise allies, becoming encumbered with values that aren’t your own, losing clarity about what drew you together in the first place.

What I worry about now is that the core values that drew us together — truth and freedom — are transforming into virtue signals about how best to ‘do’ truth and freedom. (I have been part of freedom organizations that fell apart because of arguments over who is “doing freedom right,” and who might actually be a “double agent.”)

And all of this is perfectly natural. When under pressure, and after the initial period of rallying and organizing the troops, we start to lose focus and momentum, and then we shame, devolve and disperse, fighting among ourselves until we achieve our enemy’s ultimate goal.

What’s the best way to defeat your enemy? A great offence? Powerful ammunition? No. Make them fight among themselves. Minimal effort to maximum effect.

So what should we be doing right now? What’s the prize we need to keep our eye on?

Do you know the story of Cincinnatus, the 5th century B.C. Roman consul who was called on to save Rome when it was at its most vulnerable?

Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus (left) accepting the position of dictator of Rome from the Senate, undated woodcut.

Once upon a time, Cincinnatus was a consul of Rome. But he lost his wealth, retired from his high position, and became a farmer instead. He spent his days planting wheat and tending grapes. But he was so wise and well-loved that Romans came to him from all over to ask his advice.

Rome was the strongest city in the world. But one day, a tribe of barbarians was headed towards Rome, burning and plundering everything in their path. They had sworn to conquer Rome and kill its people.

The Romans weren’t afraid — yet. After all, the Roman army was the most powerful in the world. So they sent out their most skillful soldiers to stop the barbarians. The soldiers rode out of Rome, splendid in shining armour and scarlet cloaks. The women and children cheered and waved. “Come back in glory and triumph!” they called out. “Come back in victory!”

They waited day after day after day. Finally, they saw dust in the distance: horsemen were approaching the city. But what had happened to the Roman army? Only five dirty, bloodstained soldiers were returning. They galloped through the gates into the centre of the city and told their story, gasping with pain and weariness. “The barbarians are too strong for us!” they said. “They attacked us at the narrow mountain pass! They came at us from behind and from ahead. And meanwhile they threw rocks at us from the hills above. Send help to our army at once, or Rome will fall!

The Senate was terrified. “All our strongest soldiers have already gone!” the senators said to each other. “We only have boys left. Who can lead them into battle?”

Suddenly one senator said, “Let us send for Cincinnatus. He is our only hope!”

Cincinnatus was out working in his fields when the senators arrived at his house. He washed the dirt off his hands and listened to their pleas. “If you will lead the reinforcements into battle,” they promised him, “we will make you the king of Rome.”

So Cincinnatus returned to the city with them and became their leader. He armed the boys and taught them how to fight, and then led them out towards the mountains to rescue the Roman army. Cincinnatus was so wise that this troop of boys beat off the barbarians, drove them back to the mountains, and brought the rest of the Roman army home! They marched back into Rome with trumpets blaring and people cheering.

“Be our king, Cincinnatus!” the people of Rome begged. “We will give you all the power! You can do whatever you want!”

But Cincinnatus took off his armour and gave his banner back to the Senate. “No,” he said, “Rome does not need a king. I give all my power back to the senators. They should make your laws.” And he went back to his fields and his grapes, leaving the Senate in charge of Rome.*

The sculpture of Cincinnatus in the Schönbrunn Garden in Vienna.

In 2020, we sent our strongest soldiers to the frontlines: the bravest doctors, lawyers and journalists; the most vocal influencers; the convoy leaders; the outspoken and unrelenting parents and grandparents. But at some point, the energy started to wain. Now, we are running a mega-marathon without knowing what mile we are in and with no sign of a finish line in sight. We are entering a pass and risk being stoned from all angles with no obvious defence.

So what are we doing?

Out of exhaustion, desperation or some intoxicating cocktail of both, we are praying for someone to “lead us into battle.” We are throwing all our eggs in the basket of the next, most promising leader as a ‘Hail-Mary’ attempt to save ourselves. Maybe it would be worth turning over our hard-won freedom for even the faintest hope of our salvation? And maybe doing so would be easier than doing the work ourselves? Whether it’s an incoming U.S. President or the leader of the opposition in Canada, hope abounds for a benevolent, omnipotent modern-day Cincinnatus.

The problem is, Canadians (at least) don’t obviously have a Cincinnatus in our midst. The Romans were saved, and freed, only by chance of Cincinnatus’ virtue. When he had the chance, he didn’t take advantage. He led the people. He gave his power back to the senators and went back to his grape fields.

Like the battle-weary Romans, we need a leader. But we need to make sure that we don’t turn over our freedom to whoever demands it. We need a Cincinnatus, not a Nero. We need a leader who who knows how to inspire and energize us. We need a leader to act in our interests. We need a leader to show us how to be citizens again. And if we knew more about the nature and foundation of democracy, we might know that. (Don’t get me started on the connection between our current plight and the failures of our education system.)

Is Poilievre that leader? I doubt it. He was indefensibly silent during the COVID debacle, is weak on the gender issue, and maintains a chilly attitude towards President Trump. He waffles when he needs to be convicted, trying presumably to secure broad appeal.

But he’s what we’ve got. Canadian culture has become so intoxicated with belligerent wokeism that the only way back to a more freedom-respecting democracy might be a series of slow, incremental side-steps to centre. Poilievre might be the man for that job. But that’s not saviour material. It’s acceptable-for-right-now material. Nothing to bow to. Nothing to pray to. And certainly nothing to sacrifice to.

What’s the lesson we should take from Cincinnatus?

A true leader will preserve and enhance our own power, and make our democracy stronger and richer than it is. That person will not ask more than we can give, will not expect our freedom as a deposit for our safety and security, and will never demand that we use consensus or the opinions of experts as a surrogate for our own critical thought.

We need to make good decisions when it comes time to vote, choosing our representatives well. But Canada doesn’t need a saviour and we certainly don’t need a master. We need to become masters of ourselves, our families, our homes, and our communities. We need to lead each other first in our own little corners of the world. We need to stop expecting top-down solutions and start figuring out how to rebuild ourselves from the bottom up.

*Reprinted from The Story of the World, Revised Edition. Volume 1: Ancient times, Susan Wise Bauer.

Very well said. Even if Poilievre was more of the leader we should be looking for (and I agree with your assessment of him - he's not Mr Right, he's Mr Right Now), when he takes over he'll be hamstrung by a 90% Liberal senate, a 90% liberal judiciary, and a 100% liberal supreme court - for decades. At this point it feels like Canada's conservative/freedom movement is trying to save a body that's deep in stage 4 cancer by performing a brain transplant.

Very well put! And I fully agree with you that the focus should be on our little corner of Canada, making wise-choices re: the representatives we vote for, support but importantly voice our concerns to with determination. Keep it local, and keep up our vigilance and critical thinking.

PP is, as you said, acceptable-for-right-now material but that is not a dire situation to be in, therefore some cautious optimism is ok. If the people keep the pressure up, and considering the favourable climate in the US, the Conservatives will have no choice BUT to act in the interests of people (and less so in their own self-interest if they want to keep being representatives)

Btw, and admittedly I’m a little biased in this respect, Danielle Smith is a model for good, compassionate Conservative government leadership. The support she’s getting from people and important Freedom voices across Canada ought to make us keep positive on that model swaying higher Conservative echelons to be more like her.